Cushing's Disease In Dogs: The Dog Owners Guide

Your older dog has gained weight round his midriff and his once glossy coat is now patchy in places. You’re not concerned, but then at his regular vaccination check up, the veterinarian asks questions about your dog’s drinking pattern. And yes, now you think about it, you refill the water bowl twice a day and the dog needs more comfort breaks.

The veterinarian gets a knowing look in the eye, and suggests testing for Cushing’s disease. This is a surprise because you just thought your dog was getting older. The tests are expensive, so now you face a dilemma over what’s best for your dog: Should you go with the tests or leave him be?

Cushing’s Disease Is The Great Pretender

Welcome to the confusing world of Cushing’s disease – also known in veterinary circles as “the great pretender” because it mimics old age and can be tricky to diagnose. However, the comforting thing about Cushing’s is that, in most cases, there’s no need to panic and make a swift decision about treatment. You can take time to weigh up the pros and cons in order to reach the decision that’s best for you and your dog.

Dr. Karen Becker Cushing’s Disease In Dogs Video 1 of 3

An Overview of Cushing’s Disease

Before getting into the detail let’s get to grips with the basics.

What is Cushing’s Disease?

The body needs natural steroid (cortisol) in order to function. This cortisol helps us cope in times of stress and is one of the “fight or flight” hormones. However, too much natural steroid in the long term creates problems.

The signs of too much cortisol in the body include:

- Thirst and the need to urinate more frequently

- Lack of energy

- Weight gain, especially round the belly

- Thin skin and poor coat quality

In a nutshell Cushing’s disease is a range of symptoms that occur because the body produces too much natural steroid. The condition has much in common with aging because it progresses slowly and gradually erodes quality of life.

Dr. Karen Becker Cushing’s Disease In Dogs Video 2 of 3

What If Cushing’s Disease Is Left Untreated In My Dog?

Left untreated the dog slows up and his physical appearance alters. He becomes thick set round the belly and his coat thins so you can see his skin. He may pant heavily at night and have urinary accidents. Cortisol also suppresses the immune system, so the dog is more likely to suffer from recurrent infections.

Here is a picture of what a dog with Cushing’s Disease can look like (although your dogs symptoms may look different)…

Many dogs live with Cushing’s disease and cope with the niggling health issues for months or even years. However, a small percentage develop more serious signs such as circling or head pressing, with a few dogs dying suddenly from blood clots on the lung.

Dr. Karen Becker Cushing’s Disease In Dogs Video 3 of 3

Treatment For Cushing’s Disease In Dogs

Treatment is readily available and it can reverse the signs, but the therapy is costly. The decision to treat or not depends on weighing up several factors, not least of which is expense. When it comes to Cushing’s disease, there’s not always a clear cut right or wrong course of action and it’s a matter of what’s best in your specific circumstances.

The Clues to Cushing’s Disease

Let’s start with a tale of Poppy, a patient of mine. In her younger days Poppy was a whizz at fly-ball, but lately she preferred to watch the other dogs rather than take part. Fair enough, her hips were a bit stiff, so her Mum put this new lethargy down to arthritis. And now she wasn’t so active, it seemed natural that her increasingly rotund tummy was down to burning fewer calories.

But then Poppy started having urinary accidents in the house. Her Mum assumed her dog was incontinent…and brought her to see me.

The first thing that struck me was Poppy’s urinary accidents always happened by the back door. This signals that Poppy knew she needed to go but couldn’t hold on (incontinent dogs are unaware of the leakage). When I mentioned this to her Mum, the penny dropped that Poppy was thirstier of late.

Poppy’s is a fairly typical picture, where there’s no one specific problem that makes the owner suspicious, and it’s often just one little sign associated with Cushing’s that triggers the clinic visit.

Signs of Cushing’s Disease

The signs Poppy exhibited were lack of energy, a pot belly, increased thirst, and urinary accidents. Others signs also associated with Cushing’s include:

- Heavy panting

- Pot belly

- Thinning coat and patchy hair loss

- Poor hair regrowth after a clip

- Thin skin that bruises easily

- Pigment patches on the skin

- Blackheads formation

- Muscle wastage, especially around the back end

- Increased thirst

- Increased appetite

- Shrinking testicles (In males – obviously!)

Which Dogs are Most Likely to Develop Cushing’s Disease?

Smaller breeds, weighing less than 10kg, are more likely to develop Cushing’s than larger ones. Of these breeds poodles, dachshunds, and all types of terriers tend to head the league. This doesn’t mean that Labradors don’t get Cushing’s, but statistically it’s less likely. (And larger dogs tend to get a different form – but more of this later.) This is also a disease associated with middle to old age, and is rare in young dogs.

What Causes Cushing’s Disease?

OK, we’ve already established that the problem is too much cortisol, so the question is: Why does this happen?

This excess cortisol in the blood stream may develop for one of three reasons:

1 – Medicationcontaining steroid given for long periods of time

2- The pituitary gland in the brain sends out too much “messenger” hormone

3- The adrenal gland in the tummy manufactures too much cortisol.

What Is Cortisol?

Man Made Cushing’s Disease

When high doses of steroid-containing medication are given for a long time, there is a risk of inducing a man-made form of Cushing’s disease. Typically, this happens when a pet takes steroids (such as prednisolone or dexamethasone) to treat a condition such as cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or itchy skin. If steroid is given continuously for several weeks the body may undergo the changes associated with Cushing’s disease.

This form of Cushing’s is reversible, but requires slow withdrawal of the drug. This must be done under veterinary supervision as suddenly stopping medication can induce a serious complication called an Addisonion crisis.

What Is An Addisonion Crisis?

Your veterinarian will gradually reduce the dose of the drug over time, but be prepared for it to take weeks to months to wean the patient off medication. With this in mind it is important that your veterinarian discusses the implications of long term steroid therapy before starting treatment. Indeed, if it is essential your pet takes steroids, then there are methods of dosing (such as giving on alternating days) which can reduce the risk of Cushing’s disease.

Naturally Occurring Cushing’s Disease

However, the majority of cases suffer from the natural form of the disease where the body produces too much steroid. This happens for one of two reasons, and to understand this requires a brief digression into some basic physiology.

Cushing’s Disease Due To The Pituitary and Adrenal Glands

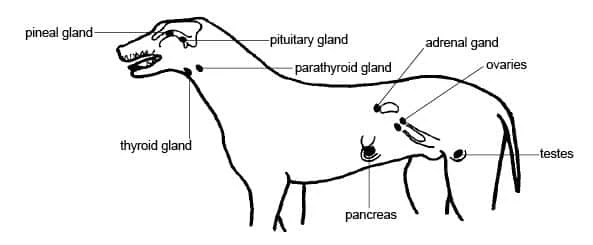

The pituitary and adrenal glands control cortisol production. The pituitary gland in the brain is the control center, which at times of need sends out messages to the “factory”, or adrenal gland near the kidney, to manufacture more cortisol.

Think of this system like ordering a takeaway pizza. You’re hungry so you pick up the phone and order a pizza. This is equivalent to the pituitary sending a message when the body needs more cortisol. Once the pizzeria receives your call the chef cooks a pizza- which is just like the adrenal gland making more cortisol.

Cushing’s disease develops when either the pituitary gland sends out a constant stream of requests (like having the pizzeria on auto-redial) or the adrenal gland goes into overdrive (the chef goes on a cooking marathon).

The Downside

In both cases, the trigger is a tumor. This can either be located in the pituitary gland in the brain, or in the adrenal gland just in front of the kidney. Now I imagine mention of a tumor has greatly alarmed you, but keep reading and hopefully you’ll feel less anxious.

The Not All Down, Downside

Pituitary tumors are more common than adrenal ones, and account for nine out of every ten cases. (Remember I said larger breeds get a different form? Well, they tend to get the adrenal form which represent less than one in ten cases of Cushing’s.)

These tumors tend to be small – around 3mm in diameter – about the size of a daal lentil. They cause problems because of hormone overproduction, rather than malignant spread to other parts of the body.

It’s only recent sophisticated imaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans that have alerted us to the existence of these tumors. Indeed some dogs had tumors up to 1cm across with no signs other than Cushing’s disease.

Exceptions

However, just like anything there are exceptions, and occasionally dogs with a large tumor (likely to have been growing for years) do show neurological signs such as head pressing, walking in circles, or seizures.

How Is Cushing’s Disease Diagnosed?

Diagnosing Cushing’s disease can give your veterinarian a real headache because there is no single test that accurately diagnoses the condition. This because cortisol is a stress hormone and released when the body is under pressure, such when the dog is ill. Thus, false positive results are common and the condition can be over-diagnosed.

A Urine Test to Rule Out Cushing’s Disease In Dogs

To get the ball rolling your veterinarian may run a urine test called a “cortisol creatinine ratio”. This test looks for the presence of cortisol in the urine, and if there isn’t any the dog does NOT have Cushing’s. (However, if cortisol is present the dog MAY have Cushing’s, or may be experiencing the stress of illness.)

The urine cortisol-creatinine ratio is a useful “rule out” test = no cortisol in the urine means no Cushing’s disease.

Screening Blood Tests To Detect Cushing’s Disease In Dogs

A thirsty dog may drink more because he has kidney disease, diabetes, or one of many other problems, so your veterinarian runs screening blood tests to rule them out. Whilst Cushing’s cannot be diagnosed on a general blood profile, there may be strong hints pointing in this direction, such as high levels of alkaline phosphatase resulting from tissue damaged by excessive steroid.

Stimulation Tests For Detecting Cushing’s Disease In Dogs

If your dog shows physical signs of Cushing’s disease, has cortisol in his urine, and suspicious hints on a general blood panel, then the next diagnostic step is to stimulate the pituitary and adrenal glands to see what happens.

There are a variety of stimulation tests which can increase the suspicion of, or confirm a diagnosis of, Cushing’s disease. Depending on the test chosen, it may also indicate if the pituitary gland is at fault (the control center set on constant auto-redial) or the adrenal gland.

These tests are:

- The ACTH (adrenocorticotrophic hormone) test

- Low dose dexamethasone stimulation test

- High dose dexamethasone stimulation test

Many clinicians start with an ACTH stimulation test, to get a yes/no answer, and then discuss with the client if further tests are necessary.

Further Tests To Determine If A Dog Has Cushing’s Disease

Further tests may be necessary for the following reasons:

- If the diagnosis is still in doubt (sadly, not even ACTH stimulation test are 100% reliable)

- For a large breed dog where there is an increased chance of adrenal disease (the treatment is different)

- Where it is important to confirm pituitary disease (such as when surgery is an option)

These further tests include:

- Low or High dose dexamethasone suppression test

- Ultrasound scan of the abdomen

- MRI scan of the brain

Low (or High) Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Tests

A small (or high) dose of steroid is given by injection and the body’s response measured. This helps differentiate pituitary from adrenal disease.

Ultrasound Scan of the Abdomen

A skilled ultra-sonographer studies the adrenal glands to look for signs of cancerous change.

MRI Scan of the Brain

The pituitary gland is like a small fleshy growth on the brain, and an MRI scan can show up a tumor.

Measure Blood Pressure

At this point, it’s also wise to have your dog’s blood pressure measured. One unfortunate complication of Cushing’s disease is high blood pressure, which may affect four out of every five cases. This can potentially be dangerous and increase the risk of stroke, sudden blindness, or even unexpected death from blood clots.

Treatment for Cushing’s Disease

This is an exciting time because a new surgical therapy is proving hugely successful. At the moment this is only available at specialist referral centers so before I get carried away, let’s look at the current medical options for treatment.

Medical Treatment

When I qualified as a veterinarian there was only one treatment – a chemotherapy drug called Lysodren (Mitotane).

Lysodren (Mitotane)

This works by destroying parts of the adrenal gland (a bit like shooting the pizza chef!) and came with some unpleasant side effects such as diarrhea, sickness, and life-threatening collapse. So it came as a huge relief when a new drug, trilostane (Vetoryl) became available.

Trilostane (Vetoryl)

Trilostane works by stopping the adrenal gland from producing too much cortisol. It is a safe and successful treatment – as long as the patient is properly monitored. The main complications occur when it does the job too well and the body becomes deficient in cortisol resulting in lack of energy, diarrhea, sickness, and possible collapse. However the good news is these side effects are reversible, when the medication is stopped.

The main drawback is the price. Vetoryl is not a cheap medication, and the costs for a large dog can be prohibitive. Add to that the cost of regular monitoring blood tests and this therapy can slip out of budget.

Surgical Options

A tumor causes Cushing’s disease and removing that tumor can cure the disease. This is where it becomes important to identify if the problem lies in the brain (pituitary gland) or the abdomen (adrenal gland) so the clinician’s first job is to localise the tumor.

Adrenal Gland Removal

Surgical removal of the adrenal gland is a demanding procedure for the surgeon, but not for the reason you might think. The mechanics of removing the gland are relatively straightforward, but immediately after surgery the patient may experience dangerous swings in cortisol levels. For this reason, adrenalectomy (removing the adrenal gland) is best done at a specialist center with 24-hour intensive care facilities. This sounds off putting, but with proper specialist care most patients overcome these complications and do very well.

Pituitary Gland Removal

This is a new and exciting treatment option. Pioneered at the Royal Veterinary College, in the UK, surgeons are able to remove the pituitary gland via a surgical approach through the mouth. This is possible because the pituitary gland sits at the base of the brain, with only a thin shelf of bone between it and back of the throat.

This technique was originally created to treat diabetic cats with a condition called acromegaly (where too much growth hormone is produced by the pituitary gland and it destabilises their diabetes) and the early work was done on cats. The potential benefit for Cushing’s disease in dogs was obvious so the technique migrated over to them – with great success.

If the idea of brain surgery sounds scary, bear in mind that most of these patients are up on their paws and eating later that same evening. The surgery needs to be performed by a neurosurgeon at a specialist center, but if you have access to these facilities then it is well worth considering.

The procedure costs several thousand dollars but balanced against the cost of long term medication and monitoring, the initial outlay may well prove a good investment.

The Importance of Monitoring

You’ve weighed up the options and medical therapy is more accessible for your pet, but your veterinarian insists on running regular monitoring tests. The cost of these tests mounts up, which leaves you wondering just how essential they are.

The ACTH test is a safety check that looks at how much cortisol is in your dog’s body. Too much – and the dog has Cushing’s disease, but not enough and he could be dangerously ill very quickly.

Insufficient cortisol means the dog can go into an “Addisonian crisis”, which can be life-threatening. In the early stages the dog lacks energy, seems weak, and has digestive upsets, whilst some progress rapidly to collapse and coma. Regular blood tests keep an eye on cortisol levels and allow dose adjustments to be made before events reach a crisis point.

What if I Do Nothing?

Every owner needs to be realistic about the depths of their pockets. You could potentially do more harm than good if you start your dog on Vetoryl but decline the monitoring that goes with it, so think very carefully before starting therapy.

Ask your veterinarian for an idea of the costs over a six-month period, including consultations, blood tests, and medication. Work out if you can budget for this or not.

If, for whatever reason, you decide against treatment then what should you expect to happen to your dog? Whilst there are always exceptions, it has to be said that an untreated dog will carry on as before for months or even years. He continues to slow up, but for the majority of dogs nothing earth-shattering happens.

His fur continues to thin, but he can wear a coat in winter. He is more likely to pick up infections, but timely trips to the vet for antibiotics can nip these in the bud. He may drink and wet more, but you can adapt and give him more toilet breaks.

Worst case scenario the risks of doing nothing include a heightened chance of high blood pressure causing complications, and eventually, the possibility of a brain tumor causing neurological signs.

High Blood Pressure Caused By Cushing’s Disease

A recognized complication of Cushing’s disease is high blood pressure. In dogs the main risks are sudden onset blindness (caused by the retina detaching from the back of the eye), a stroke, or blood clot lodging in the lungs. Unfortunately, the later may give no warnings and the dog dies suddenly. This is rare, but it does happen.

Neurological Signs Derived From Cushing’s Disease

Over the months and years a pituitary tumor may grow to a size where it puts pressure on the brain. Ultimately, this can cause peculiar behavioural changes, circling, head pressing, or even seizures.

Healthcare for the Untreated Dog

Should you decide to let nature take its course, to help your dog realize their best quality of life, I would suggest the following actions:

- Regular blood pressure checks

- More chances for a comfort break

- A stylish dog coat in winter

- Prompt veterinary attention if the dog is under the weather

Does My Dog Need to See a Specialist?

Reaching a diagnosis can be tricky, but something that your veterinarian does on a regular basis. If they suggest further tests, then it may be necessary to see a specialist for sophisticated imaging techniques such as an MRI or abdomen ultrasound scan. If surgery is top of your list, then referral to an internal medicine specialist, preferably one who works hand-in-hand with a neurosurgeon is essential.

Too Much Information?

If all this has left you reeling, then remember that a dog with Cushing’s disease has months to years ahead of them. If undecided whether to investigate, ask your veterinarian to outline the cost of treatment should the condition be diagnosed. If therapy is outside your budget then it’s better to save your money to cover the cost of occasional episodes of ill health, rather than blow it on diagnostics.

Remember, there is no right or wrong decision when it comes to whether to treat Cushing’s disease. It’s up to you to decide.

REFERENCES

- Small Animal Internal Medicine. Nelson & Couto. Publisher: Mosby.

- Notes from a lecture by Stijn Niessen. RVC, December 2014.

- Notes from a lecture by Stijn Niessen, RVC, February 2015

- Notes from a lecture by Prof Ian Ramsey PhD, BSAVA April 2014

- BSAVA Small Animal Formulary. Prof Ian Ramsey. Publisher: BSAVA publications.